By Ann Marie Jakubowski

Virginia and Leonard Woolf founded the Hogarth Press in 1917 when, for just under £20, they purchased a small hand-printing press and the accessories needed to begin printing out of their home in Surrey, England. Their first publication, Two Stories, appeared in July of that year, featuring Leonard’s “Three Jews” and Virginia’s “The Mark on the Wall.” The Press had an enormous impact on Woolf’s work: as Hermione Lee writes, the beginning of their publishing enterprise marks “a completely new direction, the beginning of a new form and a new kind of writing” for Woolf because “the new machine had created the possibility for the new story.”1

Leonard’s writings position the Press as a form of therapy for Virginia: typesetting was intended as “a manual occupation which would take her mind completely off her work.”2 Typesetting was an extremely laborious undertaking, yet Virginia’s own diaries emphasize the intellectual freedom it offered her, despite the physical toll: “How my handwriting goes down hill!” she laments in her diary in 1925. “Another sacrifice to the Hogarth Press. Yet what I owe the Hogarth Press is barely paid for by the whole of my handwriting. … I’m the only woman in England free to write what I like. The others must be thinking of series and editors.”3 Many have pointed out the ways in which Woolf’s literary imagination seems to have been shaped by her intimate awareness of the materiality of words and letters, and as it transitioned from a hobby to a professional enterprise, the Hogarth Press became a key nexus of Anglophone modernism.

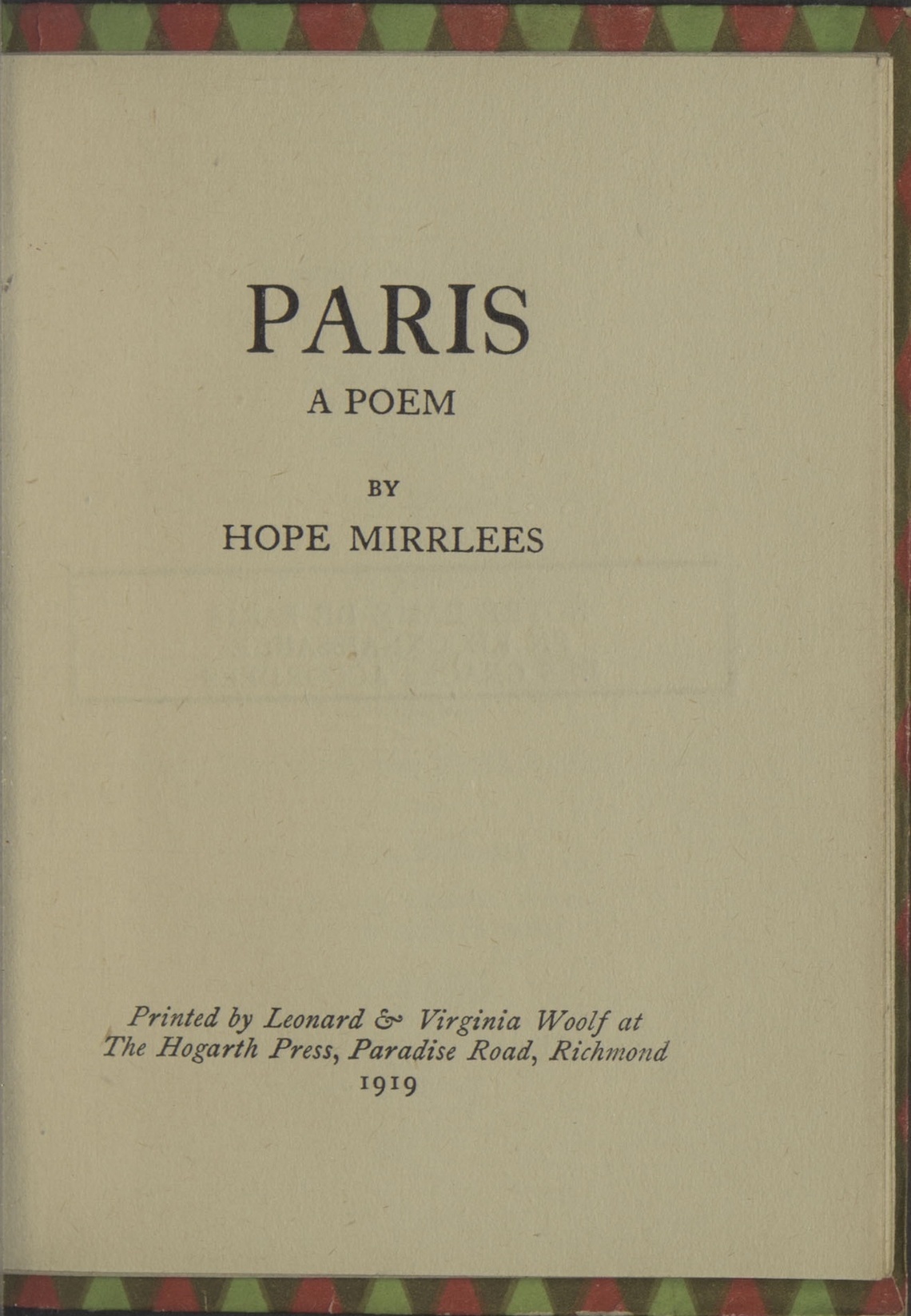

For the first five years, each book was type set, printed, stitched and bound by the Woolfs in limited edition runs, sold on a subscription basis. Hope Mirrlees’s Paris: A Poem (1919)was one of these early titles, along with work by Katherine Mansfield, T. S. Eliot, Sigmund Freud, and E. M. Forster. The press began to scale up, selling to booksellers instead of on a subscription basis and working with a commercial printer for high-demand publications such as Woolf’s “Kew Gardens” (1919) and Jacob’s Room (1922). Still, the Woolfs remained committed to “[retaining] an element of amateurism, an openness and a non-exclusive quality, that they felt might be lost if they ceded control” to a larger, commercial operation.4 Their editorial imprint reflected their own taste, and when they moved to 52 Tavistock Square, in Bloomsbury, London, the press came with them. Today, the Hogarth imprint lives on after being re-launched by Random House.

Notes

-

Lee, Hermione. Virginia Woolf. New York: Vintage, 1996, 359, 360. ↩︎

-

Leonard Woolf qtd. in Lee 357. ↩︎

-

Woolf, Virginia. A Writer’s Diary. Edited by Leonard Woolf. New York: Harcourt, 2003, 81. ↩︎

-

Southworth, Helen. Introduction. Leonard and Virginia Woolf, the Hogarth Press, and the Networks of Modernism. Edited by Helen Southworth.Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2010, 1. ↩︎