By Melanie Micir and Anna Preus

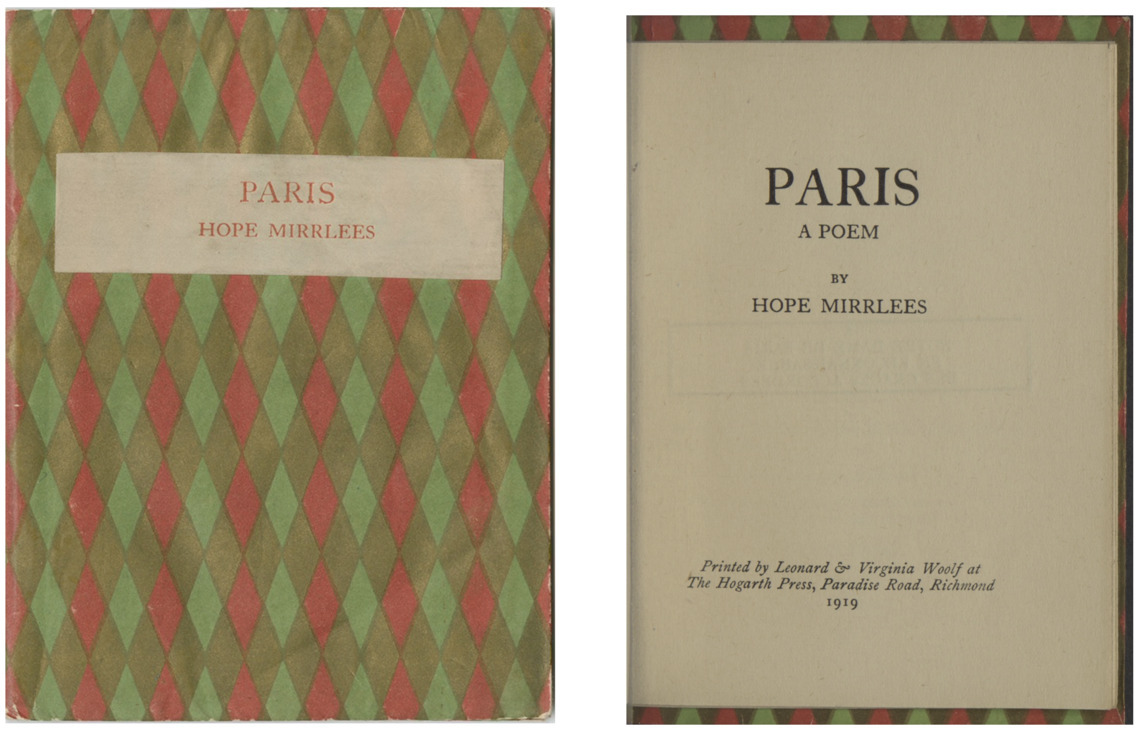

Like so many modernist texts, Hope Mirrlees’s Paris: A Poem is not easy to read. Written during 1919 and published in a print run of 175 copies by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1920, Paris is a formally experimental depiction of a woman’s movement across the postwar City of Lights over the course of a single day.

Set during the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, it is a poem that requires us to see and hear as we read: it is full of period-specific imagery (advertisements, street signs, posters in a Metro station), sounds (bits of conversation, several bars of music), and architectural references, and several sections incorporate the techniques of concrete poetry.1 Virginia Woolf, who typeset the poem, called it “obscure, indecent and brilliant.”2 And the late Julia Briggs, who introduced and provided a foundational set of scholarly annotations to the poem in Bonnie Kime Scott’s Gender in Modernism (2007), declared it a “lost modernist masterpiece.”3 Since the publication of Briggs’s annotations, Sandeep Parmar’s edition of Mirrlees’s Collected Poems (2011), and Faber’s paperback centenary edition of Paris (2020), scholarly attention to Mirrlees has grown steadily, yet Mirrlees’s presence in the digital realm remains quite limited. We created this digital edition with the hope of making Paris and the world it inhabits more accessible to contemporary readers.

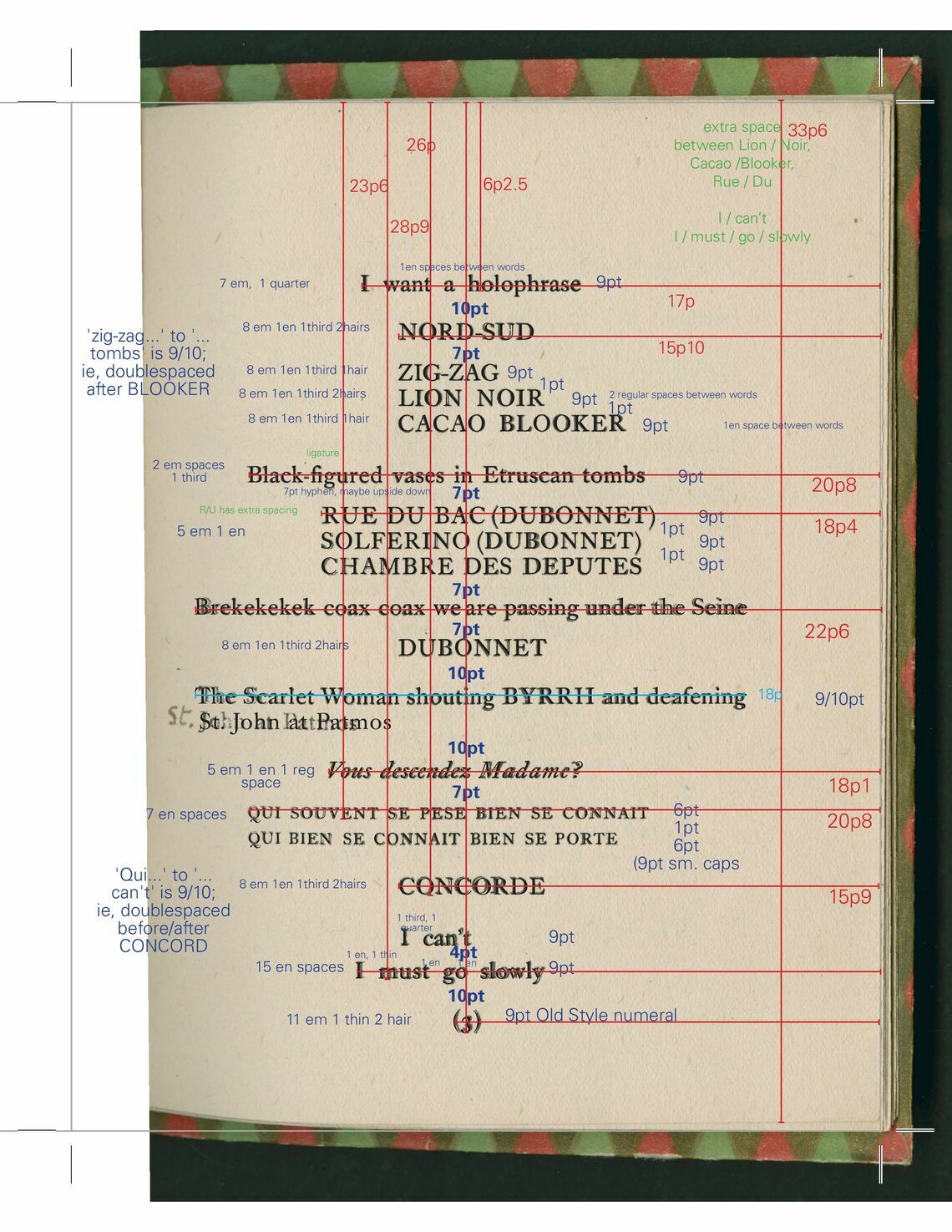

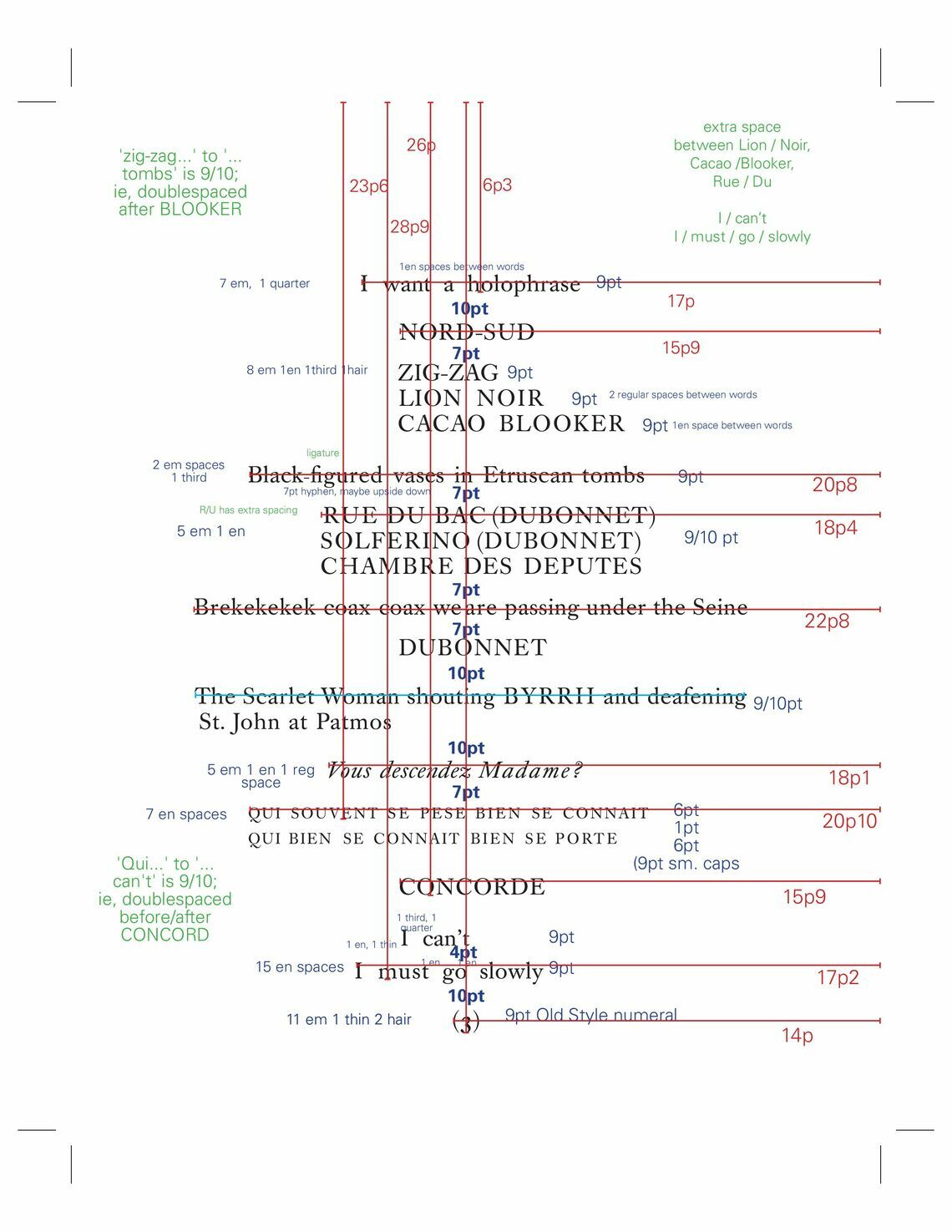

The process of re-mediating Paris has fundamentally changed the way we understand the poem. From the outset, establishing a method for digitizing the text taught us that we needed to both read and see it–to view the poem’s visual construction as constitutive of its literary meaning and to build that into our edition of the piece. Attending more carefully to the poem’s visual design, seeing the white space on every page as meaningful rather than empty, in turn forced us to see Paris as the result of a serious collaboration between the poet and her printer: Hope Mirrlees, “modernism’s lost hope,” and Virginia Woolf, “icon, celebrity, star.”4

In our approach to this project, we have explicitly viewed adaptation as a form of interpretation and collaboration. One of our main aims was to take robust digital tools and apply them to a small-scale project–to one very small book. We wanted to perform a kind of digitally assisted close reading and to re-mediate the poem in a way that aligned with the methods used to print it in the first place. The result of this effort is a diplomatic transcription of a single copy of the 1920 edition of Paris held at Washington University in St. Louis. While we aimed to follow the original text as closely as possible in our transcription, the website we created to display it also lifts the poem from the setting of each individual page, allowing it to be presented as continuous text that can be read on a variety of different devices, scaled up and down, copied and pasted, etc. We have created a number of options for viewing the text, which allow users to see the poem in different settings–as unbroken, scrolling text or as text on a page–and also provide options to view scholarly notes by Julia Briggs and contextual images from the period.5 We hope that this combination of views helps to highlight the tremendous amount of unseen, collaborative labor that went into the production of hand-printed, typographically and conceptually experimental texts like Paris.

These different options for viewing the poem also point to one of the most important ways re-mediation changes how we read now: when we access a text through a computer or other device, we expect to have choices about how we see it. By translating the poem to digital media, we are both preserving and expanding the possibilities of the text. Mirrlees’s poem is only available to us because she was persistent enough to believe her poem deserved to be published and because she met one woman with one set of type and a small handpress who chose to collaborate with her to bring her vision and her words to an audience in the form of 175 printed books. Now, by removing the text from its physical format, we have created multiple options for how it can be seen and read by many more people. What do we gain from having so many choices about how we see the materials we read? And what do we lose?

These were questions that we had to keep in mind as we began our edition of Paris and they are issues that we continue to work through today. While functions like zooming in, resizing a window, or searching a page are built into the browsers through which our site will be accessed, and are thus out of our control, there have been so many decisions we’ve had to make—so many aspects of how Paris will be seen that we’ve had to choose—that the digital edition, and the different displays and contexts we’ve chosen to offer, also represent our own collaborative labor on the project. The default, scrolling view of the poem presents Paris as a poem, a continuous literary work that exists outside of its history as a material text. The page view does the opposite; it represents Paris as a series of visual surfaces of particular size and shape. The notes view highlights the recovery efforts surrounding the poem, featuring commentary by Julia Briggs, who reignited interest in the poem. And the images view represents our efforts to make the places, people, works of art, advertisements, and events referenced in the poem more accessible to contemporary readers. Underlying all of these aspects of the site, though, are a set of documents representing the labor of multiple women who measured, recorded, and encoded data about each line and each space in the book, and who, as graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and untenured faculty members, were working collaboratively in and through various stages of contemporary academic precarity.

The question of how we see the texts we read, study, and teach is contingent upon human labor, upon who brought it into the world and how. Paris would not look how it does without Mirrlees and Woolf’s long-distance collaborative work. Our digital interpretation of their book would not look how it does if we hadn’t had to navigate different perspectives within our group on what a poem is, what a book is, and what it means to put one or both of those things online. And yet the collaboration, the differing perspectives, the shared work that goes into the creation or translation of a single literary work is what we often fail to see when we’re reading—especially in the case of authors, artists, and craftspeople working from marginalized positions within society. How would our ways of reading change if we really tried to see the work of many different people behind a single text? How might our idea of close reading change if we thought about all the decisions, big and small, that had to be made in order to for the text on our page or screen to exist at all?

Notes

-

For examples of some of the complex page layouts in Paris, see pages 4, 13 or 23. ↩︎

-

Virginia Woolf, The Letters of Virginia Woolf, vol. 2, ed. Nigel Nicholson (New York: Harcourt, 1976): 384. ↩︎

-

Julia Briggs, “Hope Mirrlees and Continental Modernism,” Gender of Modernism: New Geographies, Complex Intersections, ed. Bonnie Kime Scott (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007): 261. ↩︎

-

Julia Briggs, “Modernism’s Lost Hope: Virginia Woolf, Hope Mirrlees, and the Printing of Paris,” Reading Virginia Woolf (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006): 80; Brenda Silver, Virginia Woolf Icon (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999): xi. ↩︎

-

You can move between these formats by selecting different options at the top of the page. ↩︎